In light of the recent passing of original Dictators drummer Stu Boy King, we at the DFFD Blog are proud to share with you the only interview he ever granted, to our own Sal Cincotta, published by rock magazine Ugly Things in November 2015. Our deepest thanks to Ugly Things for allowing us to republish that article here, supplemented with some new nuggets Sal dug up from the original notes for the interview. Part I is below for your reading enjoyment. Be on the lookout for additional parts soon. (For you collectors out there, this story originally ran in Ugly Things #40, which is still available here.)

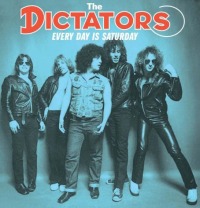

The critics adored it. The public ignored it. But in the 40 years since it first appeared in 1975, ‘The Dictators Go Girl Crazy!’ has gathered a pedestal spot as one of the purest fun albums of all time. Drummer Stu Boy King provided the beat for that punk rock masterpiece, departed from the band in the same week as the LP’s release, and hasn’t been heard from since.

With a deluxe double LP/CD reissue looming on the horizon, Stu talks for the first time ever about the band’s earliest days, their collective immaturity and inexperience, and the accidental role Neal Peart played in the band’s being dumped by Epic.

Stu, let’s go to the very beginning–what is your date of birth?

I was born on April 19, 1954. My father called me Little Hitler, long before I was even a punk rocker, because Hitler’s birthday was April 20! I didn’t catch on until a little later. I share the birthday with Andy [Shernoff], although he’s a couple years older than me. I grew up in Rockland County, New York, which was considered the sticks at that time. I was sort of a country guy.

How did you get started in music?

I started taking music lessons at six years old. The accordion was a popular instrument back in the ’60s, and my mom threw it, and lessons, at me. I hated schlepping the damn thing; it was bigger than I was! That ended quickly, followed by the violin, and maybe it was my immaturity talking, but back then, the violin was for sissies. I started on the drums at nine, and I took to them like a fish to water. With the drums, my mother got it right. I quickly became fairly competent. She bought my kit piece by piece. I had to earn a snare drum, then I had to earn cymbals, and by the time I was in sixth grade I had a little band, called the Imperial Five. We were an integrated band, which in 1965 or ’66 wasn’t commonplace. We started doing shows at school. We were doing “Psychotic Reaction,” and some R&B, “Soul Man,” a lot of Motown. The guitar player and bass players were pretty versatile.

By middle school, I was in a band called the Ravens. We were all white, mostly Irish kids, wore red sparkle vests, white shirts, black pants. We had a light show. Our guitar player’s parents had booked the band to play nice people’s back yards and parties, so we were already doing that at 13. I went through the whole school system of being in the orchestra, the marching band, the dance band, all-state competition, all-district–I did all of that stuff. I was very much a trained musician. I could play jazz, R&B, symphony orchestra stuff. If it was written, I could play it.

Music was my LIFE. Drumsticks were in my hands 24/7. Lunchtimes, when the other kids were going outside to play ball, I started giving that up–even though I played on the soccer team for a while–to go into the auditorium at school and just practice. It was my built-in mechanism, to escape my parents’ divorce. Being a child of divorce made you a cast-out kid in those days. It was very traumatic, and when my parents would be fighting, music would come into my head and drown them out. To this day, when I’m in an argument certain tunes come into my head, whether it be “Smile a Little Smile” or a Beach Boys song. It’s a coping mechanism.

After growing up listening to ’50s and early ’60s stuff, and playing that type of music, around 1967 I started listening to harder rock. I loved Blue Cheer, Cream, Procol Harum and Hendrix, and started listening to early Ted Nugent, the Moody Blues, CCR.

What was high school like?

Although not too many people up in my neck of the woods shared my interests, I did have a lot of friends at Ramapo High School. The school had a tremendous arts program, and got into NYC’s St. Patrick’s Day parade in 1970 and 1971. We have never since done that. It’s very difficult for a marching band to get into that parade–synchronizing 180 people in an orchestra, when people are smoking pot and doing LSD–it’s not easy to keep that together!

We entered and won a couple “Battle of the Bands” contests while in high school, with my brother Merrill on bass, in a band we called The Pig Newtons. I came up with the name after watching Merrill tear into a sleeve of the cookies and telling him, “Merrill, you eat like a pig!”

Where did the “Stu Boy” nickname come from?

I got it in high school. I was the type of kid who would do just about anything. I was always laughing and was a very happy guy. I guess they called me Stu Boy because I was always outside doing crazy stuff. A good nickname is hard to come by, and I still answer to it! As long as you don’t call me “Stewie.”

How did you get involved with the Dictators?

One of the guys I knew in high school, Bob Kaplan, who was a little older than me, was friends with Andy Shernoff. This goes back to 1971 or 1972. Bob was living up in Rockland County, but he came from Queens, and he knew Andy before he moved up here. Andy was going to SUNY New Paltz, and Bob would go and hang out up in the dorms at New Paltz. Andy wasn’t a musician at that point. All of us went to a little club where the college kids would go listen to music and drink beer, and we would watch a band called Total Crudd, who had a roaring monster of a guitar player named Ross [“The Boss” Friedman/Funichello].

Through Bob, I became friends with Andy and with Ross before there was a Dictators, before those two even got together! Ross was a wicked player, even at a very early age! He was LOUD, FURIOUS, and certainly turned up the decibels. I knew I wanted to jam with that guy. I remember this one song called “My Coca Cola Can,” so already he had the signs of a punk, even though that word wasn’t being used at that time. He was grinding out that kind of sound long before the Dictators. A lot of people were emulating Clapton, or Page, or Jeff Beck–not Ross. He had his own sound already.

A little bit later in 1972, after high school graduation, at 18 years old, I went to England, because I wanted to see the English bands play, and learn to play in their style. I’d go through Melody Maker’s ads, knock on doors and audition for bands. I got to speak with Stan Polley, who was president of American International Management, and he got me in contact with Badfinger! They had interest in using me, but the concerns were that I was too young, and that I was on a passport–how long could I stay? I practiced with them a few times and ended up living in their practice studio in London. The band was very nice to me, and they used to torture their drummer every time his wife caused trouble by telling him, “If you can’t go and play with us, we’re putting Stu in!” Meeting the band did lead to me getting my first studio session ever, for EMI, a song called “My People in The Village” by Al Turner. It was a reggae song and was very popular in Europe. I also got to play a huge gig with two members of Elephant’s Memory at the Marquee in London, in maybe November or December of 1972, opening for Chris Spedding’s band Sharks. I don’t remember what we were called.

The whole UK experience was euphoria for me. But a few weeks before I went, in July or August of 1972, I spoke with Andy, and he told me he was starting a band with Ross. They were still up in Kerhonkson, and they wanted me to be in the band. Period! The Dictators were starting before I even went to England in 1972! I remember that I had all my drums in my car with Andy, and we were driving up to the house they shared to jam together. It was nighttime, we were in the middle of nowhere, and he couldn’t find the house! I was planning on staying up there and playing with them, to see if it was going to work out.

We tried playing, and we couldn’t get it together. There was a lot of frustration over it. The Dictators, at that point, were more than a clique than a band. You have to remember, Andy and Scott Kempner hadn’t played their instruments for very long. Musically, things were just not working out. So I went to England and never got to play with the beginnings of the Dictators. I might have changed my trip completely, if I’d known that, lurking in the background, were Murray Krugman and Sandy Pearlman [managers and producers of Blue Oyster Cult]. It might have changed the whole interpretation of the foundation of the band to begin with by having me in the band. It might have changed the creative part of it as well.

When I came back to the States, I played with some of my mentors in the Silver Caboose for a while. They were a tremendous band, with great vocals and musicianship. They did an album under the name Anthem on Buddah [in 1970], on which they changed their sound to try to be a Chicago-type band, and it just didn’t work out. I just loved playing with them, but there was an eight-year age difference between me and them. I was hungry to go to the city and become successful. These guys, they didn’t share my ambition. They had already been there and back, done TV shows, put records out, and had no desire to try again for the big stage. They were making good money doing what they were doing. But I wanted to move forward, so I took my EMI tape and started going to the city. I loaned that tape to one of the members of the Tokens, who said he’d use it to try to get me work, and never saw it again.

I was playing a lot at that point, and I got into another band called the Virgin Woolies. Good-looking guys, Stonesy type of sound, original music. We played a lot at an all-girls college, Marymount College in Tarrytown. Not a bad gig when you’re 19 years old! We had a great audience of all Catholic schoolgirls. But they didn’t want me to play any rolls. They were holding me back, and I was a little young to be held back.

Then the Dictators came calling again for a drummer.

Part II coming soon!